Some notes on the mysterious Henry Cort

Including a half-hearted stab at topicality quickly abandoned in favor of mustier pursuits.

Here’s a nice, arcane controversy. It’s of the moment, but not too of the moment. Red meat to us here at the Genealogian.

Henry Cort (c1740-1800) was an English ironmaker who developed a new and more efficient way of refining raw iron into wrought iron. His invention was key to revving up the Industrial Revolution, right up there with the steam engine.

And now here we are, staring into glowing rectangles together. Apart.

Last summer, the British researcher Jenny Bulstrode made a splash with a peer-reviewed piece arguing that Henry Cort stole his methods from enslaved Jamaican laborers:

The British Industrial Revolution is marked by economic and societal shifts toward manufacturing — away from largely agrarian life. Many technological advances powered this change.

One of the most significant innovations was called the Cort process, named after patent holder Henry Cort. The process takes low quality iron ore and transforms it from brittle, crumbly pieces into much stronger wrought iron bars. The transformation is cheap, allows for mass production and made Britain the leading iron exporter at the time.

But after analyzing historical documents, Jenny Bulstrode, a historian at University College London (UCL), found that the process was not actually created by Cort.

"It's theft, in fact," says Bulstrode.

Sounds ironclad ha ha!

But it turned out her whole argument was built on supposition and inference, the few thin reeds of fact questionable at best, but sometimes demonstrably false. You can find that whole argument summarized by Ian Leslie here. And summarized again here.

Other than Leslie (glancingly) nobody’s hit the genealogical angle. Here’s Bulstrode’s original argument on Henry’s “cousin” John Cort, from whom Henry is supposed to have learned the techniques of Jamaican metal workers:

Two months later, master of the ship Abby, John Cort, arrived in Kingston . . . Later that same year he was returning from Jamaica in convoy, when the Abby was separated and taken off course. ‘[L]eaky, sickly and short of provisions’, they abandoned their intended destination of Lancaster. By dint of ‘incessant pumping’, with just ‘three days bread’ to spare, they weighed in at Portsmouth, where John Cort’s ‘cousin’, Henry, ran a struggling ironworks.

When John Cort arrived in Portsmouth, he found his cousin an imminent bankrupt, deep in debt, surrounded by heaps of Admiralty scrap iron and no way to work it without incurring further losses. As Henry Cort watched his investments sink in the heaps of rusted scrap, he heard the latest news from Jamaica . . . a foundry where a team of 76 Black metallurgists had developed an ingenious way to turn scrap metal into valuable bar iron. He learned of John Reeder’s foundry, turning a clear profit of £4,000 a year, equivalent to a relative annual income of £7.4 million in 2020 sterling.

As a young man, Henry Cort inherited a ‘private fortune’ from his father who was ‘extensively involved in trade at Lancaster’. Britain’s fourth largest port for the human trade, the enslavement system has been described as Lancaster’s ‘staple’ and ‘life-blood’. Cort and his family members were embedded in this system. His older cousin and patron, Jane Cort of Lancaster, accumulated property and capital investing in the human trade and enslavement. Her brother and his son were Lancaster-based West Indies merchants, together with their cousin shipmaster of the Abby, John Cort.

I did you a great favor and removed the footnotes, so allow me to clue you back in. Bulstrode’s only evidence that these three Corts (our man Henry, Capt. John, and Jane of Lancaster) were related is the will of Jane Cort, proved at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in 1799. Is that enough to tie everyone together?

Well, it certainly ties Jane to Henry. Almost right off the bat, we get:

I give and bequeath to my cousin Henry Cort late of the Navy Office Crutched Friars London but now of Gosport in Hampshire Gentleman and to his sister Jane Cort in Standing Harfordshire spinster the sum of one hundred pounds a piece . . .

The ironmaker Henry had indeed started out his career with the Navy in London, then moved to Gosport, the home of his in-laws’ ironmongery. We’ll get back to sister Jane of “Standing” in a moment. But this confirms that the testator Jane Cort of Lancaster considered our Henry to be her “cousin.”

Jane then names some other relatives—a niece by the name of Hathornthwaite, and a nephew also named Henry Cort, who was the son of her deceased brother Thomas Cort of Lancaster.

And then, there it is!

… a sum of two hundred and fifty pounds to my nephew John Cort now in the West Indies.

We should note that Jane Cort made her will a long time before she died. So while it was proved in 1799, all of these people were named as they stood in 1789.

That’s pretty much all Bulstrode has to tie Henry to spinster Jane and Captain John. And it’s far from nothing. To sum up, there was an unmarried Jane Cort of Lancaster who died there in 1798. Henry Cort the ironmonger is her cousin. And John Cort the shipmaster is her nephew. Unless both of Jane’s parents were distantly related Corts, it’s probably fair to say Henry and John were closely related, not more than second cousins.

This all turned out to be entirely beside the point. Bulstrode got a lot wrong, but her genealogy was fine.

The Genealogical Mystery

I talk a good game about the value of a genealogical mystery. And when I started writing this, I didn’t expect there to be much of one here. Henry Cort lived in a time and place of abundant record-keeping. Either he and Capt. John were cousins or they weren’t. I’d find out exactly how they were related, and that would be that.

Events, not for the first time, have embarrassed me. Henry Cort, as I learned, has enjoyed the adulation of a tiny fan club for about two hundred years. And they’ve been working assiduously this whole time to figure out what town Henry hailed from, let alone who his parents were. And that’s even with the Jane Cort will, which researchers first discovered in the 1980s.

Credit where credit is due, that was the work of Reginald Arthur Mott, who published a biography of Cort in 1983 in which he also revealed one of the earliest records of the ironmonger’s existence, the 1763 sale of a Hertfordshire farmstead:

9 and 10 May 1763: Draft lease and release, Henry Trott of Standon, farrier, to Henry Cort of Crutched Friars, gent., farm in Colliers End for the sum of £825.

Other than the Standon connection, which ties him to his sister Jane living there in 1789, this tells us that Cort had some serious dough to throw around, even at a young age. Jane the will-maker, a wealthy woman herself, was the youngest daughter of an earlier Henry Cort, mayor of Kendal in Westmorland. Mott’s collaborator E.W. Hulme had a theory:

Cort, according to Hulme, was not born in 1740, as his gravestone has it, but in 1742, being most probably an illegitimate son of a Mayor of Kendal, born at Ellel, near Lancaster.

Hulme had discovered a near-contemporary source placing Henry’s birthplace in Ellel, now mostly the site of Lancaster University. There is a problem with that theory: the parish registers for Ellel Chapel exist, recorded in the parish book for Cockerham, and I reviewed them. There’s no Henry Cort in there. No other Henrys either. What, you’re not going to baptize the boy? I doubt that.

I mean, here’s the thing. Yes, “cousin” could mean a lot of things. But we can be pretty sure it does not mean “legitimate nephew,” because Jane specifically calls other people her nieces and nephews. And those people were demonstrably the children of her siblings. Was this a delicate way of referring to the illegitimate son of one of her brothers or sisters? Sure, that’s one possibility. But we can be quite sure Henry won’t be much further removed than first cousin, especially if he was in London by the time he was 23 and the elder Jane was in Lancaster the whole time. How, otherwise, would they have known each other?

It is weird, though. There’s only one Cort man baptizing children in the Lancaster area around the time of Henry’s birth: that’s Thomas Cort, Jane’s brother. And his son Henry, baptized 23 Feb 1734/35 in Lancaster, was one of the nephews named in Jane’s will, a merchant who himself died in 1799. Merchant Henry left money to the two daughters of his late brother, John Cort of the island of St. Eustatius. Presumably that was Captain John.

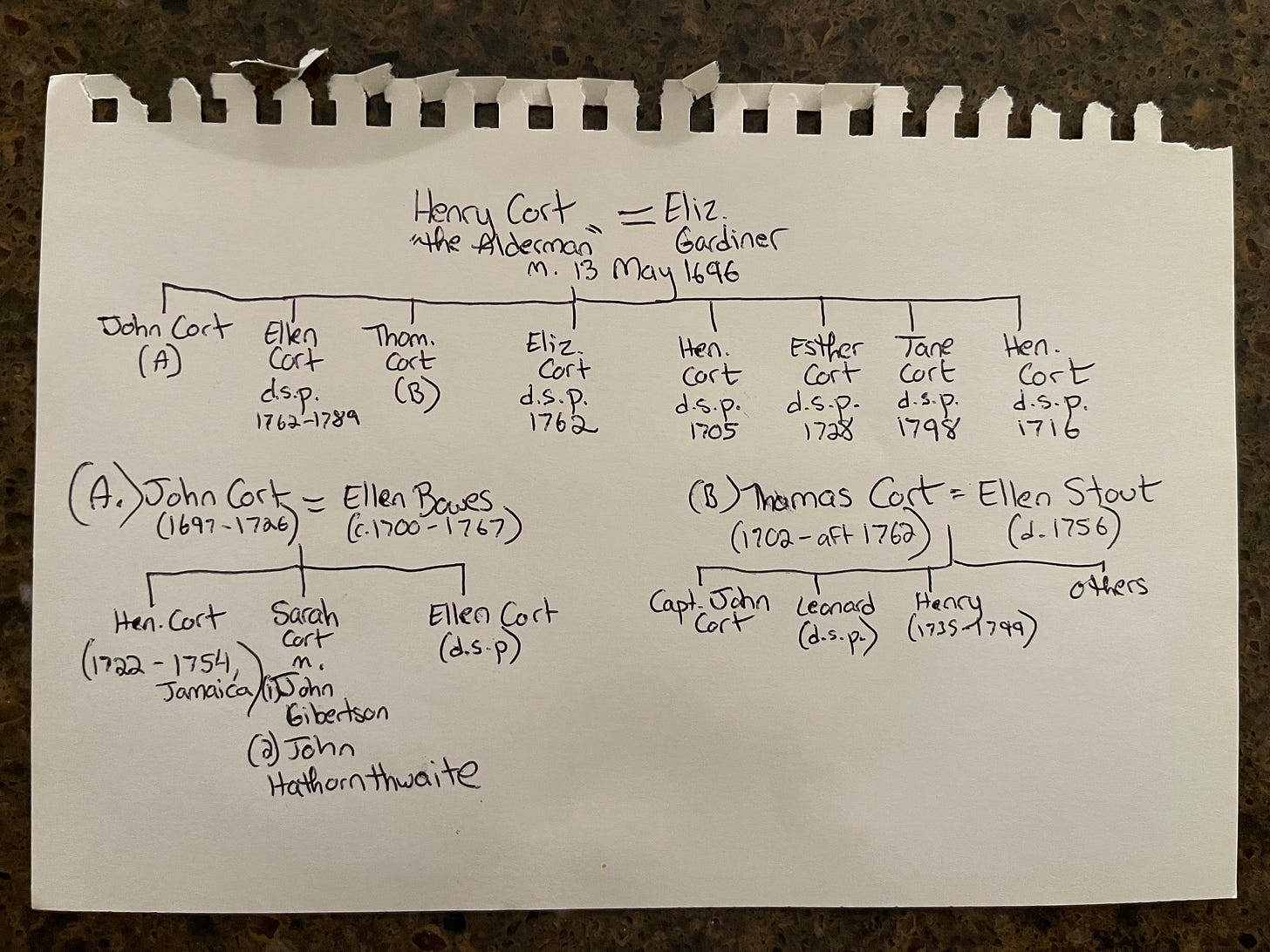

I better draw you a chart.

So here are some live possibilities:

Henry Cort was the child of one of Jane’s siblings, or even Jane herself. If he was born between 1735-1745, brother Thomas, sister Elizabeth, and sister Ellen were all living and of age to be his parent.

Thomas already had a son Henry (the “nephew” Henry named in Jane’s will), and frankly it would be incredibly weird for him to also name his illegitimate son Henry. But you could imagine a scenario. Maybe he had nothing to do with the child’s upbringing or naming, and his mother came from a line of Henrys, or wanted to rub it in Thomas’s face that he was the father by naming the child after Thomas’s own father.

Elizabeth left a will herself in 1762 and she doesn’t name any children. Not disqualifying, but a strike against the theory.

Ellen was named co-executrix of her sister Elizabeth’s will, but does not appear in sister Jane’s. Thus she probably died between 1762 and 1789. But that’s about all we know about her.1 She wasn’t married in 1762, at about 62 years of age herself, so its not likely she ever married.

Henry Cort was a very late-born illegitimate child of Henry the Mayor of Kendal, Jane’s father.

This is Hulme’s theory mentioned above, under which Henry would be Jane’s much younger half-brother.

Note that the mayor would have been well into his seventies. And he was a widower at that point. Why not just get married? Also, why wouldn’t this birth be recorded somewhere?

And also, hold up here with all those bastardy theories. Don’t forget that our Henry had a sister, Jane. One illegitimate child is perhaps easy enough to cover up or remove from the contemporaneous records. Two, though? Now you’ve got a secret family. The three Cort sisters never married, but they were quite eligible, wealthy maidens. What’s the version of the story by which one of them has a long-term liaison with one man (or short-term with two men), including some very obvious evidence of said relationship, but they never get married, even as a cover story? Unlikely.

Henry was an illegitimate (or legitimate for that matter) son of Jane’s nephew Henry Court, son of her brother John.

That’s the going theory here, which Wikipedia has tentatively adopted.

I found some evidence for that, which I don’t think anyone else has published:

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:939F-DZJC-H?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AVHDB-2HX&action=view&cc=1827268 Maybe you can’t make that out. It shows the baptism of a Henry Cord in Saint Catherine’s Parish, Jamaica, to Henry and Elizabeth, on 22 May 1740. Got him! Right?

Not so fast. The Jamaican Henry died intestate, so there’s not much to pull from his probate file. The “Salt History” site says the administratrix was Henry’s widow Ellen, but it was actually his mother Ellen. That’s the same widow Ellen Cort who left a will in 1767, after the ironmonger Henry—and likely his sister Jane—was supposedly back in England and making a living. Widow Ellen Cort, who under this theory would have been grandmother of both Henry and Jane, names neither in her will. Indeed, she gives virtually her entire estate to her granddaughter Ellen Hathornthwaite, with some legacies to her daughter’s stepchildren, the other two children of John Hathornthwaite.

I get that an eighteenth century widow might leave her illegitimate grandchildren out of her will. But this seems a rather extreme case, where even if her one living grandchild dies before 21, the back-up beneficiaries would be unrelated step-grandchildren and an unrelated son-in-law. Surely you’d throw the two Cort kids a bone before your in-laws?

Henry Cort was literally Jane’s first cousin, or perhaps first cousin once removed.

This is almost certainly the answer. The problem is that we don’t know where Mayor Henry Cort came from, so we don’t know his siblings.

What do you all think?

The Ellen Cort whose will was proved in Lancaster was not this Ellen, but the widow of her brother John Cort.