I’m Nobody! Who are you? Are you – Nobody – too? Then there’s a pair of us! Don't tell! they'd advertise – you know! How dreary – to be – Somebody! How public – like a Frog – To tell one’s name – the livelong June – To an admiring Bog!

I love a good historical footnote. We should all be so lucky. Let’s face it. Most of us don’t have a Caesar inside of us, waiting for history to call. You’re not a dormant Boudica, ready for action if you’d only stop snoozing your phone alarm. What’s more, do you really want to be? That’s a lot of uninvited trouble. You don’t need that. Not to mention the Ides of March.

I’d rather be Caesar’s college roommate, or Boudica’s blacksmith. But I’m a retiring type. Maybe you’re a megalomaniac.

I love the minor figures because I love the grand sweep of history. The people at the margins—the footnotes—they tie it all together. My own relatives, to the extent they had any role to play, connect me Kevin Bacon style to the world-bestriding historical figures I love, but do not envy.

For who did Alexander put to the sword? Our ancestors.

Who did Antony harangue at the Forum? Our ancestors.

Who did Napoleon send to their deaths at Austerlitz, Borodino, and Waterloo? Our ancestors!

And to whom did Emily Dickinson send a sharply-worded letter because of some hidden offense and possibly because he stopped responding to her letters? Say it with me now.

My half-first cousin, six times removed!

The Early Life of “Belvedere”

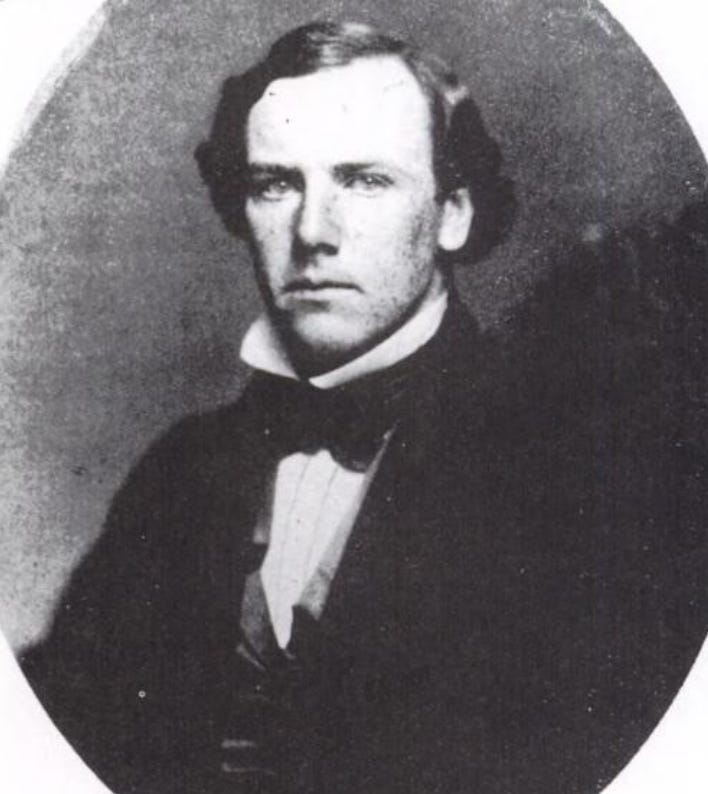

There he is, the old so-and-so: James Parker Kimball.

James was a Vermonter by birth. His father, another James, was for many years a “city missionary” in Boston, which is exactly what it sounds like. He was on an internal mission to the poor and downtrodden of New England’s metropolis. James’s mother sounds great. The massive Kimball genealogy of 1897 says she was “one of the early teachers in Bradford Academy, and a woman of great ability.”

Bradford Academy is long gone, but it was a secondary school along the lines of Philips Exeter and Andover. Unlike those schools, Bradford was co-educational from the very beginning, and always with a strong weight toward girls.

Indeed, James Parker’s grandfather, yet another James, was one of the founders and original trustees of the Academy. The Kimball Genealogy’s got more great stuff to say here:

He had a high spirit and a passionate nature. He was a good hater when occasion demanded. He was large, regular featured, and of sanguine temperament.

What more could you possibly need to know about a man?

His grandmother, Ruth (Kimball) (Kimball) Kimball1, was my 6th great-grandmother. The book is silent on her, but we can be sure this was a woman who really loved her family.

James was the product of two smart and public-minded parents. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, I will assume he shared in those qualities.

Meeting at Amherst

Emily Dickinson…you know Emily Dickinson. Emily was from Amherst. In fact she lived in town her whole life and her immediate family was deeply rooted in town and academic life. You might say the Dickinsons and Amherst grew up together. When Emily was nine years old in 1840, she was enrolled at Amherst Academy, and she’d remain in schooling there for the next seven years. In September 1845, when Emily was 14, young James Parker Kimball arrived at Amherst College.

And here, if were writing of the fortuitous meeting of two titanic historical figures, would begin our real story. But alas, there is but one titan here. Here begins the footnote.

After her graduation from Amherst Academy, Emily spent about ten months at a seminary in neighboring South Hadley (later Mt. Holyoke College) before returning to her parents’ home in March 1848.

The first indication that James and Emily knew each other at all comes in January 1849, when Emily was at home, and only a few months before James was to graduate. Her brother Austin was in the class of 1850; maybe he introduced them. But Emily lived only a short stroll from campus, went to school nearby, and would’ve had any number of opportunities to socialize with the students.

In January 1849, he inscribed for her a brand new book of poetry.

Scholars can date very few of Dickinson’s over 1,800 surviving poems to the years before 1858. Of course, that doesn’t mean she wasn’t writing poetry in her earlier years. She may, like many embarrassed artists before and since, have destroyed her juvenilia.

But whether she was writing or not, her “mature” style—that which made her posthumous reputation—was surely not yet developed. Now imagine you’re a scholar of poetry. You see the poetry scene before Emily Dickinson. You see the poetry after. And you see her. This woman never left the hills of central Massachusetts.2 She was a townie! And yet what she produced was outrageous, sui generis, the genesis of something entirely new.

Miss Dickinson, where do you get your ideas?

If you ask them when they’re still alive, you’re a fawning simpleton at a book signing. If you “ask” after they’re dead, you’re a scholar.

Belvidere and Philopena

The book, if you didn’t follow the link (shame!), was an 1849 edition of the poetry of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.

Holmes père was one of the most popular American versifiers of the Victorian era, right up there with Emerson, Longfellow, and the other “Fireside Poets.” And if the image of a little Victorian family cozied up in the front room by a crackling fire, listening raptly to mother and father declaim “The Wreck of the Hesperus,” doesn’t warm your cold, Tik Tok’ing heart, I’m not sure what you’re doing here. We must be friends in real life.

Holmes, unfortunately, was no Longfellow. He was certainly no Emerson. And take that from me, who is predisposed to give him every possible benefit.3

He said it himself:

Child of the ploughshare, smile;

Boy of the counter, grieve not,

Though muses round thy trundle-bed

Their broidered tissue weave not.

That is, don’t quit your day job.

And indeed, Holmes was a much better doctor than he was a poet. This is a guy who, through careful empirical study, argued the germ theory of disease—and thus the need for doctors to keep bedsheets and hands clean—years before the practice was widely adopted.

We know that someone was reading the Holmes poem I quote above, because there’s a little penciled bracket, faint but purposeful, hugging two of the lines. Maybe that was James marking it for Emily, or perhaps Emily marking it for herself. Maybe it was some other family member, years later.

But what about that inscription? Under “Miss Emily E. Dickinson,” James wrote one Greek-sounding word in quotes: “Philopena.” You might think “Philopena” was a cutesy nickname he had for Emily. She certainly had a few for him, and we’ll get to those later. But for the true meaning, I too must offer up my thanks to Isidore, the patron saint of the internet.

Another and highly reprehensible way of extorting a gift is to have what is called a philopena with a gentleman. This very silly joke is when a young lady, in cracking almonds, chances to find two kernels in one shell; she shares them with a beau; and whichever calls out ‘philopena’ on their next meeting, is entitled to receive a present from the other; and she is to remind him of it till he remembers to comply. . . .

There is a great want of delicacy and self-respect in philopenaism, and no lady who has a proper sense of her dignity as a lady will engage in anything of the sort. [LanguageHat (this guy has been blogging continuously since 2002!]

Now, based on that, wouldn’t you say there’s a pretty good chance that James was Emily’s “beau?” I would. Picture the scene. Cracking almonds together under a campus poplar.4 Emily gets a two-in-one. They half jokingly refer to the latest foolish fad. Philopena! But sure enough, Emily invokes her rights the next time they meet, and James proudly grabs his latest purchase from one of the most popular poets of the day, and jots down an inscription.

A book of poetry! A book of poetry gifted to the girl who would become the greatest American poet of the nineteenth century, and perhaps the greatest of any century. Of course, he couldn’t have known that then, and indeed, as events would have it, he never would.

To get right down to it, it’s hard to see how James’s gift to Emily had much to do with her future work. But Holmes’s poetry wasn’t nothing to her. Even the most radical artistic breaks, upon reflection, are in dialogue with the past of their forms. And, don’t forget: Emily was eighteen years old, and eighteen is an impressionable age.

Speaking of impressions: James was a handsome guy, don’t you think? Maybe that’s why Dickinson called him “Belvidere.”

An Oblique End to the Relationship

The next winter found Emily still in Amherst. James had moved in with his own family in Oakham, Mass. (thanks 1850 census), but teaching school in nearby Ware. We know they were writing to each other. But the correspondence does not survive. We can only guess at their final break from Emily’s letters to her close friend Jane Humphrey. She mentioned him once in a letter of January 23, 1850. But first note how, at nineteen years old, she is already reckoning with the permanent disappearance of her friends and family:

Did you know that Payson had gone to Ohio to live? I was so sorry to have him go - but everyone is going - we shall all go - and not return again before long. Kavanagh says "there will be mourning - mourning - mourning at the judgment seat of Christ"5 - I wonder if that is true? I had a letter from Lyman a little while since - you may read it sometime.

James doesn’t merit much ink, frankly. A couple sentences in the postscript:

I have written to Belvidere - and young "D.D." will feel some things I think - at any rate I intended he should - and wrote accordingly. It would have done your own heart good.

And it doesn’t seem he wrote back. For a couple months later, Emily wrote of him again to Jane:

No news from our "Theologian" Jennie, he must have "made way with himself" - I really dont care if he has. I am hushed as the night when I write her, and of him I hear not a tiding. I only prayed for pride - I have received yet more; indifference, and he may go "where he listeth," and never a bit care I. Something else has helped me forget that, a something surer, and higher, and I sometimes laugh in my sleeve. Dont betray me Jennie - but love, and remember, and write me, and I shall one day meet you.

I think it rather a silly exercise to try and guess the exact nature of this brief, antediluvian relationship. She was upset with James, that seems clear. And his theological inclinations, or maybe just his piety, seem to be playing a role. Else, why is he “D.D.,” our “theologian?” Why may he go “where he listeth,” as went the wind in the gospel of John?

Some scholars believe James must have played a role in Emily’s brief personal religious revival of her teen years, and that these letters show the beginning of her disillusionment. And that doesn’t seem entirely off base, as I said. But doesn’t it sound like something more personal was going on?

In any case, where did he goeth?

After a couple years of teaching and apprenticing to the law, James found his true vocation—which Emily apparently knew all along. He went to Andover Theological Seminary, was ordained, and was called (pretty shockingly, I would think), to the far side of the Mississippi: Keokuk, Iowa. It was during a spell back east that he married a Granby, Massachusetts local: one Mary Barton Dickinson. Coincidence? Sure, I guess. Mary and Emily were only very distant cousins.

James and Mary had a daughter in 1860, their first child. And they named her Mary Emily Kimball. You’re gonna tell me she was named for James’s mother. Sure. I guess.

They had seven more children before Mary (Dickinson) Kimball died, in 1872. In the meantime, James spent a decade as a Congregationalist pastor in Falmouth, Mass., then another six years at the church in Haydenville. In 1876 he took a job as secretary and treasurer of the Boston Tract Society, necessitating a move to Jamaica Plain, Boston. And wouldn’t you know it, in 1881 he pulled up stakes again, for what would be his final home and resting place: Amherst. His Amherst obituary says he was already suffering apoplectic attacks (strokes), and it sounds like he went to Amherst to retire. Was it the pull of the old alma mater, relations of his first wife, or something else?

James bought a house on Amity Street with his second wife Jennie, and they settled in with his six children of all ages. Once again, he was a leisurely stroll away from Emily Dickinson.

Two years after that, he died there at only 53. Four years later, Emily followed.

We love a tale of youthful romance, lost and rekindled. We’d settle for a late-life friendship. But keep in mind what we’ve actually got: a book, an inscription, and two nearly opaque references in the surviving correspondence of a woman whose surviving correspondence runs into the thousands of pages.

Candidly, I doubt Emily thought much of old Belvidere after he left town.

But here at the Genealogian, James, we remember you.

Err…don’t ask.

I can’t help but note that her 5x great-grandfather Nathaniel Dickinson, originally from Billingborough, Lincolnshire (credit to genealogist Clifford Stott), was buried in the Old Hadley Cemetery in 1676, a mere five miles from the Dickinson “Homestead” in Amherst. That’s a 225 year stretch of continuous habitation in a tiny patch of the Connecticut River Valley—from Nathaniel’s settling in Hadley in 1661 to Emily’s death in 1886.

How could I not love the man who wrote an ode to his great-grandmother, thanking her for making his existence possible?

OK, it was January. And if you’ve ever experienced a Massachusetts winter (during the “Little Ice Age,” no less) you will find it implausible that they were cracking nuts on the quad. By the by, when’s the last time you cracked an almond?

A Longfellow reference, speaking of.