Kind of an omnibus follow-up to Was Elvis Jewish?, here.

If you weren’t in the New York area, or if you aren’t the kind of sad and frustrated obsessive who follows local politics, you may have missed this story. Before George Santos, there was Julia Salazar.

Julia Salazar is now a New York State senator. Lucky for you (and lucky for me), I don’t write about politics. Especially not the grimy, workaday, inside baseball of political campaigns. I leave that to literally the entire rest of the internet. So I’m picking up this story a cool five years after the last person stopped caring about it. That’s what I love about family trees. They’re evergreens. I keep getting older and they stay the same.

Salazar is the daughter of a Colombian-born father and an American mother, supposedly of Italian-American background. And—she’s Jewish. Except she was lying about that last part:

But Salazar differs from Ocasio-Cortez, Nixon, and the rest of her cohort in one interesting respect: the state Senate candidate is the only one to have emerged from a specifically Jewish corner of leftism. She “comes from a unique Jewish background,” as The Forward put it. “She was born in Colombia, and her father was Jewish, descended from the community expelled from medieval Spain. When her family immigrated to the United States, they had little contact with the American Jewish community, struggling to establish themselves financially.” From early 2016 through May of 2017 she was a Grace Paley Organizing Fellow with Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ). Her fellowship biography identified her as senior editor of Unruly, the “intersectional blog” of the anti-Zionist and pro-BDS Jewish Voice for Peace’s Jews of Color and Sephardic/Mizrahi Caucus. Her last publicly listed job before running for office was as a staff organizer for JFREJ, which is a New York-based left-wing social and activist organization . . .

. . . Going in reverse chronological order, Salazar has also been a contributor to Mondoweiss, an IfNotNow demonstrator, a Bridging the Gap fellow through Brooklyn College Hillel, a World Zionist Organization campus fellow, a co-founder of the Columbia University chapter of J Street, an AIPAC Policy Conference student attendee, and founder of the university’s Christians United for Israel (CUFI) chapter. For much of the five years leading up to her campaign, Salazar dedicated herself to explicitly Jewish causes, often in a professional capacity. If she wins, her identity as a politically radical working-class Jewish immigrant will have helped take her to a position of formal power and authority. Based on interviews with former acquaintances and an examination of her writings, social media postings, and publicly available documents, it is an identity that is no less convincing for having been largely self-created.

That’s from Armin Rosen at Tablet Magazine, who pretty thoroughly debunks the idea that Salazar had any conception of being Jewish before her early twenties. In response, Salazar subtly tweaked her identity to instead say that her father had a “Sephardic surname” in which she’d taken an interest, soon leading to her conversion to reform Judaism in 2012.

I’m going to leave the thorny questions of personal identity to more subtle writers. We live in an age consumed with such inquiry, and if you’ve got the itch, serious journalism has your fix. But I’ve got my hammer, and I see a nail.

I.

There is a category of genealogical truth that I don’t often find discussed. I’d call it the trivially true. The trivially true is a function of a deeper genealogical truth. In fact, it’s one of the deepest: each of us has a ton of ancestors. Certain things flow from that, but they’re not terribly interesting. The classic example: if you have any European ancestors within the past two hundred years or so, you are descended from Charlemagne. Now, that fact writ large is interesting. But as it pertains to any individual person, who cares? It’s trivially true. Of course you’re descended from Charlemagne. It’d be more interesting if you weren’t, though impossible to prove.

Same would go for a descent from Confucius in China. We hear about documented lineages from the philosopher, and those are very cool, don’t get me wrong. But what’s cool about them is the documentation. The fact of the descent is trivial. Confucius lived more than a thousand years before Charlemagne. That’s so long ago that there’s a good chance every—I don’t know—Bengali!—is also descended from him. I mean, we’re talking, what, 75 generations ago? To say each of us had more arithmetical ancestors than people living on Earth at the time would be to vastly understate the case. 2^75 is scientific notation territory.

Again, the documentation is cool. The mere fact of descent is trivial.

So let’s bring this concept to bear on Iberians and Sephardim.

From Wikipedia, since it’s kind enough to cite its sources:

Historic accounts of the numbers of Jews who left Spain are based on speculation, and some aspects were exaggerated by early accounts and historians: Juan de Mariana speaks of 800,000 people, and Don Isaac Abravanel of 300,000. While few reliable statistics exist for the expulsion, modern estimates by scholars from the University of Barcelona estimated the number of Sephardic Jews during the 15th century at 400,000 out of a total population of approximately 7.5 million people in all of Spain, out of whom about half (at least 200,000[95][96]) or slightly more (300,000) remained in Iberia as conversos;[97] Others who tried to estimate the Jews' demographics based on tax returns and population estimates of communities are much lower, with Kamen stating that, of a population of approximately 80,000 Jews and 200,000 conversos, about 40,000 emigrated.[98] Another approximately 50,000 Jews received a Christian baptism so as to remain in Spain; many secretly kept some of their Jewish traditions and thus became the target of the Inquisition.

Both of the modern estimates say there were 200,000 or more conversos in Spain after the expulsion. That’s a lot of people. Add two more facts to the mix: (1) a lot of immigration to Latin America occurred in the 1500s, or roughly fifteen generations ago; and (2) speculatively, but I think reasonably so, a converso was more likely than the average Spaniard or Portuguese to emigrate. So, say you’re a modern-day Latin American and you’re about half Spanish by ancestry.1 You’ve got 32,768 ancestors fifteen generations ago. Half that is 16,384. To be fair, a good portion of your immigrant ancestors probably came over in the 19th or 20th centuries (especially if our hypothetical descendant is Argentinian, Brazilian or Cuban), but let's say that doesn't matter because they were in Spain fifteen generations ago either way. Conversos were roughly 2.6% of the Spanish population, but we’ll say they were much more likely to emigrate and peg them at 4% of your Spanish ancestors. Rounding down, that’s 655 people.

There’s often a ton of pedigree collapse in Latin American family trees, so let’s slice that in half, to 327. 327 ancestors of recent Jewish descent. Yes, this calculation is a colossal fudge and I’m baking in a million assumptions, but notice how extremely far we are from zero.

It is, in my opinion, trivially true that many Latin Americans are descended from at least one, and probably several, Sephardic families in early modern Iberia. It is therefore of minimal genealogical interest to simply have such a descent. It is, on the other hand, of great interest if you can prove it.

II.

Because let’s be clear about Salazar’s original claim here. She’s saying that 500 years ago, she had one ancestor who was Jewish. And she has no proof, not even a family tradition. Instead, she probably based it on a highly dubious “surname list” making the internet rounds. There are obviously Sephardic surnames. But, at least as far as I know, there are no converso names. Converso names are the same as Spanish and Portuguese names. A lot of converts took the name Mendez or Mendes, but that’s because a lot of Spaniards and Portuguese already had the name. The same is likely true of Salazar. There was, for instance, Gonzalo de Salazar, a “new Christian” who happened to be the first child baptized in Granada after the reconquista.2

The upshot is that you can’t just go by surname. It’s a lot like the coat of arms racket. Your last name might be Hamilton. That doesn’t entitle you to the coat of arms of anyone else who happens to share the surname. You’ve got to be the right sort of Hamilton. And you’ve got to be the right sort of Salazar.

But say the senator were right. One ancestor, 500 years ago, was a convert. That is trivial. If she could document the descent, I would honestly find that pretty damn interesting. But my interest, for the nth time, would be in the documentation. Can you show your descent from the first Salazar in the Americas? That’s cool. Can you further document, maybe through inquisitorial records, that the immigrant Salazar was a converso, descendant of conversos, or even more exciting, a so-called crypto-Jew? Fascinating!3

But, DIGRESSION AHEAD, in a perfect world it would only fascinate a bunch of genealogy nerds.

What do I mean by that? I mean that if the general public cares about a public figure’s remote genealogical descent, something has gone wrong. The general public is caring about the wrong things. When someone with no other interest in genealogy hits you with: “did you know George W. Bush is related to all the other presidents and they’re all descended from English Royalty?” you’re about to get an earful about Lizard People and the Illuminati. Set aside the fact that the assertion—which I used to see a lot—is dead wrong. Even if true: who cares? Why should it matter to anyone but genealogists?

Similarly, it strikes me as faintly unsavory, if not unstable, that Julia Salazar would seek—and evidently find—her core personal identity in a single man living in the early days of the printing press who probably has a million other descendants.

III.

Finally, finally, because we actually are all genealogy nerds here, let’s get to the substance of Julia Salazar’s specific claim. She is not claiming that she comes from recent Latin American Sephardic ancestry. Many Sephardim and Mizrahim left the Ottoman Empire for South America in the twentieth century, but they aren’t her ancestors. Instead, it’s her immigrant ancestor, who must have arrived in Colombia some time between 1492 and 1700.

Let’s dig in!

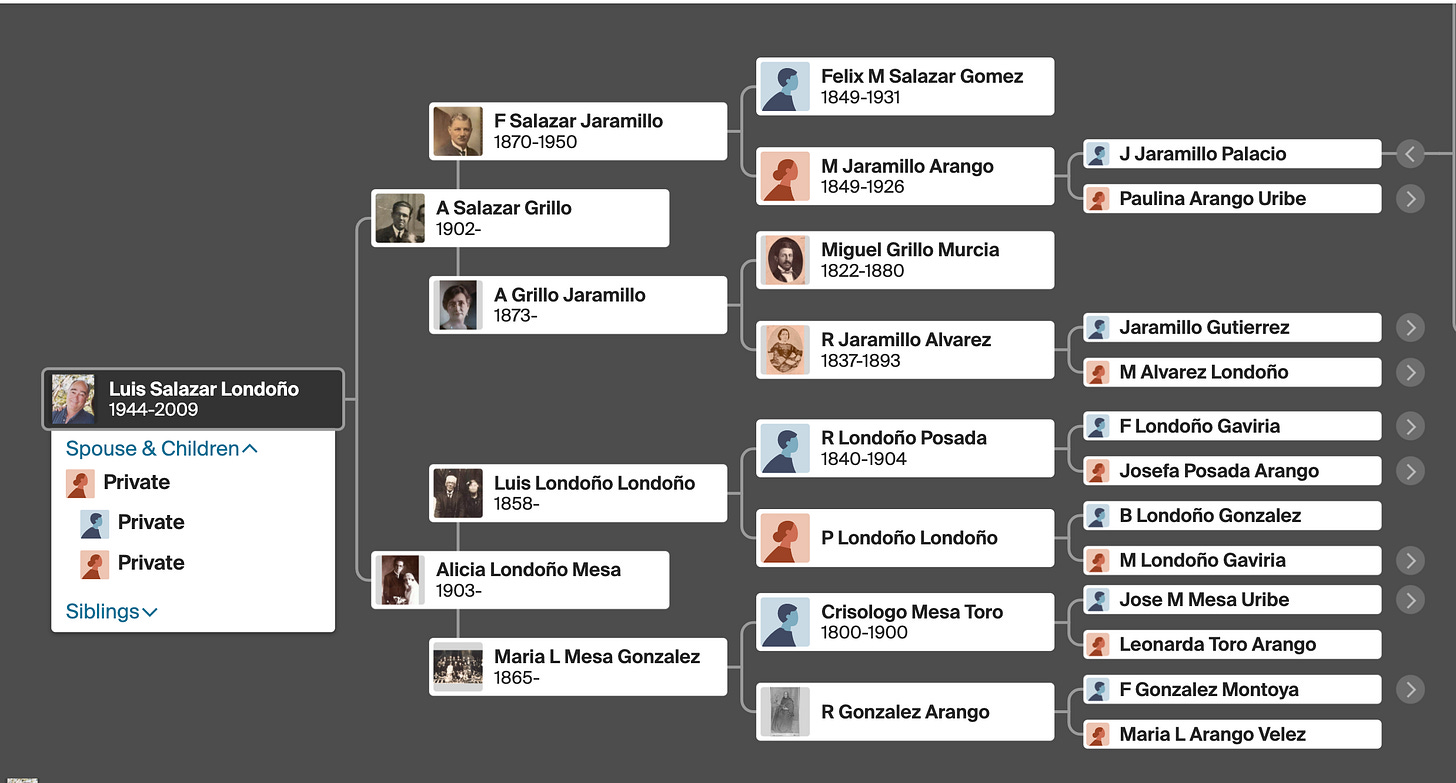

Salazar’s father is easy enough to find. Luis Hernan Salazar was born in Bogotá, 23 April 1944. From there, I’m pleased to say most of the work is already done for us.

We’ll get to the ancient Salazars in a minute. But I do want to point out, by the by, that this is a star-studded family tree. The great-grandfather, Félix Salazar Jaramillo managed the central bank of Colombia and was the national finance minister. His father Félix María Salazar Gomez was an immensely successful businessman, wealthy landowner, and mayor of Manizales, the capital of the Colombian coffee industry. Her Arango ancestors were closely connected to an attorney general of Colombia, a first lady, and a president. Her first cousin a few times removed was the archbishop of Medellin. Basically, the Salazars and their kin were (and probably remain, if I were to guess) the country’s conservative ruling class.

I went ahead and double-checked the agnatic Salazar line using FamilySearch’s Colombia, Catholic Church Records collection. Here it is, starting from Julia Salazar’s grandfather:

Alejandro Salazar Grillo, bapt. 16 Feb 1902 in Marinilla, Antioquia.

|

Félix María Salazar Jaramillo, bapt. 20 June 1870 in Manizales, Caldes.

|

Félix Salazar Gomez, bapt. 25 Feb. 1849 in Salamina, Caldes.

|

Mariano Antonilo Salazar Serna, bapt. 12 May 1822 in Granada, Antioquia.

|

Ramon Nepomuceno Salazar Gomez, bapt. 3 Sept. 1792 in Marinilla.

|

José María Salazar Gómez, bapt. 27 Nov. 1754 in Marinilla.

|

Juan Ignacio Salazar Hernández, b. circa 1720 (married in 1748).

That’s as far as I can get skipping through the indexed records.

You may not know this—I certainly didn’t—but Colombia, and the departamento of Antioquia in particular, has a rich genealogical tradition. Rather like French Canada, there was a small founding settler population, explosive population growth, and a rich parochial record. Among the great researchers was Gabriel Arango Mejía, the author of the two volume Genealogías de Antioquia y Caldes. Arango is reputed to be a careful scholar, so I (caveat lector) am assuming his work on the early Salazars is solid (though between you and me I’m a little disturbed he rarely uses dates). Pardon my sloppy translating, but here’s what he’s got:

This surname stems from very distinct origins in Antioquia.

. . .

[One of them] was don Antonio de Salazar, whose descendants make up the majority of people of the name in eastern Antioquia.

He was a native of Simití, in the state of Bolivar, son of don Pedro de Salazar and doña Jacinta del Castillo. He married doña Juana Henao, daughter of Melchor de Henao and doña Juana Losada.

Their children were:

1.— Don Miguel, married to doña Maria Hernandez, daughter of don Juan Hernandez and doña Maria Flor Giraldo.

Among their children, we find:

a.— Don Juan Ignacio, married with doña Maria Josefa Gomez, daughter of don Antonio Gomez and doña Jeronima Jimenez.

And that takes us back to solid ground.

Naturally, if you’re bold enough to Google Pedro de Salazar, you will find a few more generations in Spain—the Basque country in particular—but there are no sources connecting don Pedro with his alleged Spanish parents. Given that, I don’t feel comfortable taking the line any further, especially given how common the name Salazar was. Per Arango Mejía, there were multiple Salazar colonists in Antioquia alone. For our purposes, the important thing is that there is no indication the family was Jewish.

You eagle eyes might have noticed a few Arangos in Julia Salazar’s family tree. Antioquia was a small world. The senator and the genealogist are second cousins, thrice removed, through the 18th century Medellín couple Pedro Pablo Arango and Maria Botero.4 That's just one of their connections. I'm sure there are many more.

IV.

I mentioned that it’s probably not only the surname list that was giving the senator her ideas. The people of Antioquia, the capital of which is Medellín, have a reputation. No, not that one—but it’s not unrelated. In Colombia, Antioqueños are known for their entrepreneurship, and they’ve historically dominated various industries in the country. You can see this in Julia Salazar’s own ancestry. But obviously, you can’t just let people be good at things. We need to explain it somehow. And one explanation people apparently found very persuasive is that those people must be “Jews.”

Ann Twinam walks through the history of this particular fable in “From Jew to Basque: Ethnic Myths and Antioqueño Entrepreneurship,” and the upshot is that denizens of Bogotá seem to have come up with the theory in the early 1800s, and it gained currency over the years to help explain the outsize success of Antioqueño merchant families like the Montoyas, Arrublas, and Aranzazus. No mention of the Salazars, but great-great-grandfather Felix was surely conspicuous in the capital at this time.

By 1925, the story took absurd root in America, and in classic Tom Buchanan style, no less. Wrote Dr. Miller to the Rockefeller Institution:

The department of Antioquia has the greatest surface and population and is the most important in the Republic of Colombia. It derives its name from the town of Antioch in Syria.

Its population is almost all of Jewish origin, for it was here that they established themselves when they fled from Spain. Owing to the disposition inherent to the race, the Antioqueños have succeeded such that their department is the first in finance and in industry in all the country.5

As Twinam recounts, it was Arango Mejía himself who disproved the myth once and for all, as his magisterial work on the 16th and 17th century settlers of Antioquia demonstrated that none of them were of Jewish origin, at least not in any way that could be easily discerned. Undeterred, outsiders decided the industrious Antioqueños must be Basques instead—there must be something different about those people! Twinam quotes Emilio Robledo capturing the spirit of the inquiry:

[Colombians] would prefer the invasion of a real Jew, or even a Yankee, to that of the Antioqueño.

Why does that help? Allow me to shovel some. When your neighbor is more successful than you, you want one or both of two things to be true: (1) there’s something pathological about her success, like she’s done a deal with the devil; and/or (2) she’s so utterly different from you that a comparison would be ridiculous. You’re playing different games on different planets. The latter explanation is why the Sultan of Brunei can’t make you feel badly about your tiny house. The guy is in a different league, operating by different rules. Whereas if your buddy from high school makes $10 more than you, that’s grounds for an existential crisis.

As to the first point, it doesn’t deliver the same complete absolution, but it’s certainly nice to tell yourself that your neighbor works all the time, neglects her family, has no hobbies, etc.

“The Jews,” to a devout early modern Catholic creole, check both boxes. To you, they’re an alien people. And yes, maybe their ancestors converted, but are they really going to heaven? Unclear. Who cares if their house is bigger than yours? Whereas if Nacho the country bumpkin shows up in the big city one day in an ill-fitting suit with empty pockets and five years later he’s the biggest coffee wholesaler in the hemisphere…you’ve got to ask yourself, “maybe if I had worked a little harder…”

V.

At long last, is Julia Salazar Jewish? That’s a question for the Rabbis. I can tell you this much: if all she’s got is the genealogical claim (“the Salazars were Jewish, so I’m Jewish”), then she hasn’t got anything at all. There is no such documented ancestral link. Say there were an undocumented one? Then she’s welcome to join one of the world’s least exclusive clubs.

Here’s what I suspect happened, and I’m going to be charitable. At some point in the early nineteenth century, the people of Bogotá noticed something. Immigrants from Antioquia seemed to be dominating the commercial interests of their fine city.

“This is strange!” they thought. “Surely these provincials aren’t better than us. They must be Jews!”

And people found that idea attractive, I think for the reasons above. So the myth takes root. People love genealogical myths, as we know. And they are very stubborn things. This one, though it was overtaken by new myths (the Basque theory) and prideful countermyths (we’re Spaniards and Mestizos too, we’re just better than you), was never extirpated, even though it’s been thoroughly and painstakingly disproved.6 Witness this phenomenon, among others I am sure.

By the time Salazar’s father was born, maybe his family took a certain pride in the myth, even going so far as wanting it to be true. Confirmation bias being what it is, no one gave the story a hard look. They took it at face value. Julia, as a young evangelical Christian, found the idea immensely attractive. She Googled her last name, Gonzalo de Salazar popped up. Family legend confirmed! And maybe she didn’t know much about genealogy, or about history, as most people don’t, and it made total sense to her that a single Salazar amongst her millions of ancestors sufficed to make her Jewish. That furthermore, hundreds of thousands of Antioqueños had carefully observed their “true” religion behind closed doors for four hundred years and no one had any proof.

I find it entirely plausible that she believed these things. It’s just that she was wrong. And even if she were right, she was wrong.

Maybe this is a strange thing to say, but your ancestors are not a means to an end. They are not hats to be tried on. They are not swords, and they are not shields. They are real people who lived once. They do not serve you. You serve them.

I know every fiber of our beings tells us otherwise, but we don’t matter more than the dead just because we happen to be alive right now. Not anymore so than we matter more than our own unborn great-grandchildren.

So when someone like Julia Salazar uses her ancestors to her own ends (and I don’t care how pure they are) without making the slightest effort to actually know them, I am offended. I am offended as a genealogist. You don’t have to like these people. You may wish you had different ones. But make an effort.

An average Colombian would probably be a bit more European than that, but this is not an exact science. Or a science.

Gonzalo took his surname from his mother, but it was his father’s family (de Guadalupe) that was of known Jewish origin. So never mind.

We needn’t relegate ourselves to abstractions. Check out this research on the Coryell family of colonial New Jersey, long assumed to be of Huguenot origin. It’s fascinating stuff, and it’s great genealogy. It is also, I would say, not at all trivially true that any descendant of colonial North Americans would have at least a few Sephardim ancestors. In fact, it’s not true at all. The Coryells are a rare exception.

At the same time, I’d find it ridiculous if any Coryell descendant on the basis of this research decided that they were in any practical sense of the word “Jewish.”

And they are both related to the artist Fernando Botero, another Antioqueño. The first Botero in Colombia came from Genova.

I’m not a big fan of moral presentism and I don’t like to gratuitously slur our predecessors for their bad ideas (we’ll be getting the same treatment in fifty years time, make no mistake), so let’s also congratulate Dr. Frederick A. Miller for directing an anti-hookworm campaign in Colombia that surely saved many lives and is more public-spirited than anything I’ve ever done.

I say that, but let me be perfectly clear. The myth, which by all accounts was invented in the past three hundred years, is based on nothing. The genealogical research proves only this much: that zero, or nearly zero, of the hundreds of founding Antioqueño families, give any indication of New Christian origin. That does not mean that new evidence couldn’t crop up that shows that two hundred years before their immigration, these Spanish families were predominantly Jewish. But that would be a pretty extraordinary coincidence and I don’t think it likely.